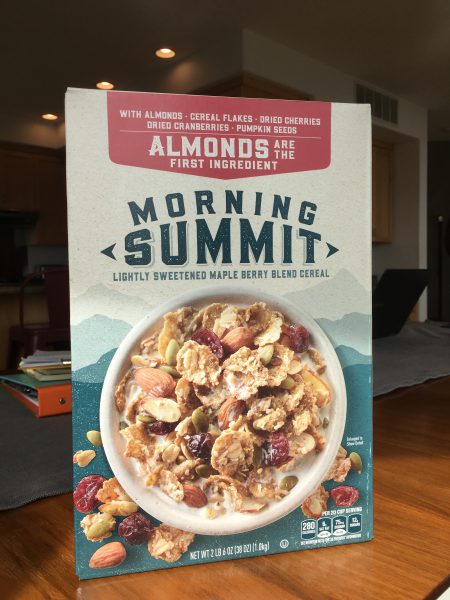

My new favorite cereal costs twelve dollars a box.

That’s $12–not $1.20. Yep, “expensive” cereal has jumped from six dollars a box to twelve dollars a box—only a one hundred percent increase. Why?

Because people like me will pay it.

Why will I pay it?

Because I’m forty-six years old and it’s sold at Costco. And buying that cereal is my way of going back and assuring my broke, twenty-six year old self—who couldn’t even afford a Costco card—that cleaning other people’s toilets while nine months pregnant was worth it. (We were apartment managers in a sketchy Portland neighborhood. Our car got stolen the first night we were there. But that’s this whole other story.)

Some people feel they’ve “made it” when they buy a big house or take a cruise; I feel I’ve made it when I buy a twelve-dollar box of cereal at Costco. Because in my post-apartment-managing mind (which is also riddled with PTSD), a twelve-dollar box of cereal is a luxury reserved for the wealthy—which, if I buy it, obviously includes me.

This logic applies to all of my Costco purchases. The more overpriced junk I buy, the more fully I feel that I’ve arrived. Last week I found myself—the mom who’s always researched recipes, made weekly menus, typed up shopping lists and then hauled my three kids to myriad stores to find the best deal—pulling pre-made meals out of the Costco cooler and tossing them into my cart. Pre-made, people. I used to coupon, for Pete’s sake. What had I become? Not just glamorous and glitzy (though there’s certainly that) but also lazy and careless. Much as I’d like to blame this buying-instead-of-cooking on getting older and savvier, the hard truth is that I’m also getting older and lazier, at about the same rate. Am I proud of this newfound apathy? No. Am I too old and lazy to change it? You bet I am.

Which barcode sounds good for dinner, dear?

When I was twenty-six, I knew plenty of forty-six year-old mothers who refused to cook for their families; they even seemed proud of it. “I don’t cook for my kids anymore,” they’d announce, shaking their heads, “it’s just not worth it.” I’d smile and nod while judging them ferociously. What kind of mother doesn’t cook for her children? I’d think, my whole twenty-six years brimming with indignation. Doesn’t she care if her kids eat?

Now that I’m forty-six, I understand: NO. AS A MATTER OF FACT SHE DOES NOT CARE IF HER KIDS EAT. Because her kids will no longer give her the stinking time of day. Her kids don’t even show up til after ten most nights. The years of mommy-coddling-littles are long gone; it’s blood-for-blood with these teenagers now.

Add to that the New Money Factor (see: twelve dollar box of cereal) and you have the perfect formula for spending money instead of time on our children. It gets a bad rap in certain parenting circles, but we Costco moms know better. Some things just work: Ungrateful kids + crappy reheated food = more Netflix time for us.

So the next time our teen comes tromping through the front door wailing “Mom, I’m STARRRRVING! What’s for dinner?” we will be justified in our smiling reply: “Cereal, darling.” And if they say “Cereal? Again?” we’ll simply point to the cost and say “See how much Mommy loves you? Twelve whole dollars worth, that’s how much!”

They might have a rebuttal here—something about health and nutrition and a mother’s loving care and blah blah blah, but we won’t have to hear it because we’ll already have Netflix cued up and turned up—way, way up. The kids can fend for themselves; The Crown starts in November. I’m just saying.