Tomorrow, I will drive my daughter—the second of my three children—eight hundred miles to her freshman dorm, hug her goodbye, and drive back home without her.

I’m trying to picture my life after she’s gone, and it looks to me something like this:

Except in my mind, the blank space goes on forever. I know this is not accurate–or so they tell me. But it’s how I feel.

I once read how a mother’s child isn’t just someone she loves, it’s a place that she goes. Her child is her home. How beautifully true when her children are young; how devastatingly true when they are grown. The very place we feel trapped in at the beginning is where we’re desperate to return to at the end.

I dropped a friend off at her home last week and her teenage daughter–all blond-ponytailed and summertime glow–met her on the lawn. She made a gesture toward the dog and said something to her mom and they both started laughing. Their backs were to me and I was glad, watching a moment longer than I should have. Their chatter rose across the yard then fell silent on my windshield, barring me entry to their private world of mother-child. I drove home in the baked gold of late afternoon and though I didn’t mean to, I started to cry.

I thought it would be easier letting my second child go. Practice and all that, right? Nope, not easier. Not at all. Because after my first left, and I’d felt all the feels, I finally settled into new territory: the Land of the Changing Family. It took some time but I ‘d made peace with it. I’d built a new home and I felt safe there. But now, as Child Two follows Child One out into the world, I’m once again exiled—banished from her gaggle of friends bursting through the front door, noisy Sunday dinners and crusty cereal bowls left in the sink after a midnight laughfest. She acts like it’s no big deal, this Child Two–picking up and leaving and taking my hard-won territory with her.

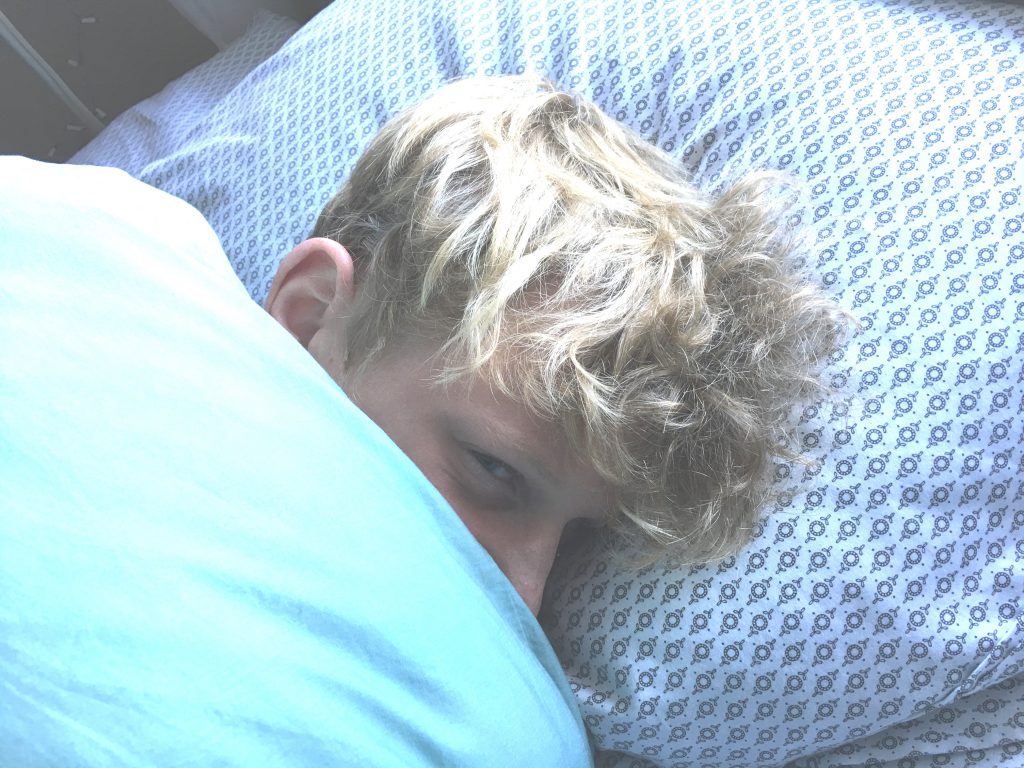

Which leaves me alone with Child Three, in all his charming and boyish abundance. I’ve found solace in that steaming mass of white hair since he was three, and for that I am thankful. (Is it the hair that makes the head hot, or the other way around? Mysteries.) I suppose–I know–that the trick to all this is finding a new home with just him in it. It’s always been there, overlapped with his sisters’, but now it will stand on its own. Surely it’s a home with light and heat, songs and jokes, and will offer me the refuge I seek. Because whether we have one child or ten, they fill up our lives like a vacuum, exacting our love to distraction. A mother’s devotion has never been determined by numbers. Thank goodness.

And that must be the blessing in the heap of all this change, that we get to peel layers off of the family stack and discover the wonders of the individual. We get to move, once again, into a new home. It means leaving the old one and wow is that painful. But we’ve done it before and we’ll do it again and we’ll be markedly better for it. After all, we’re only here, today, because our own parents—ages ago—allowed us to up and leave them. We took their homes and their youth and their hearts away with us, but still they let us go.

I’m glad that they did. I’m glad that they did and I’m glad that I’m here and I’m glad that I was given the chance to walk the sunlit path of Growing Up. I needed that adventure and so do my children. So I am determined. I will take a deep breath, cry a little in the afternoons, and give it to them.

(p.s. they better appreciate it.)