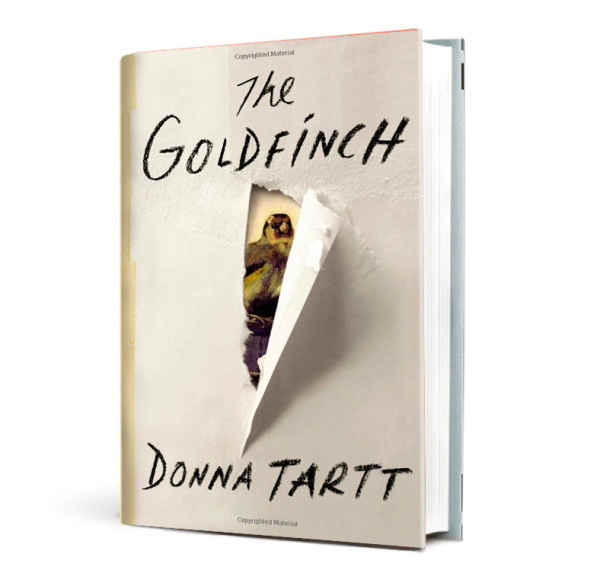

Finishing a great book—even a sad book—fills me with a kind of geeky exhilaration that I can only compare with finally being invited to sit at the Cool Table in the seventh grade cafeteria. (Okay, so maybe it only happened in my dreams. But the feeling was all too real.) I know a book’s good when I forget that I’m reading it and find myself just hanging with my brave new friends in the brave new world that the author has invented. So it was with this little number:

Now before I wax too poetic about the tragedy and triumph of this novel, let me disclaim: this book is not for everyone. It pulls the reader into a world of wealth and art that eventually spirals into a world of crime and drugs, with all the despair—and language—that follows. I like to fancy myself a reader with high but realistic standards; I do not cringe at a little language or reference in an otherwise thoughtful book, but I do cringe at an excessive or gratuitous use of the same. This book made me a cringe a little. But I couldn’t stop reading it. (I tried. But I couldn’t.)

And though the language was, at times, excessive, I never found it gratuitous; it brought the story to light in a believable (though somewhat disturbing) technicolor. The language was not titillating; more like heartbreaking. But still, it could be deemed offensive, and thus a deal breaker, for many readers—a position I respect, as I often take it myself. (Except when I don’t.)

However. When we consider our “standards” for literature, I hope we consider standards of originality and craftsmanship, voice and detail, and careful, honest dialogue. I hope we do not choose our books solely by an isolated standard of “clean” or “not clean,” wherein the cheapest rhetoric can past muster while the truest often fails.

But why do I go on? I’m sure you know what you like and don’t like. As for me, I liked this book. A lot.

The Goldfinch taught me about paintings and antiques and museums and estate sales and art dealers and drug dealers. It took me to the monied world of the New York elite and the desperate world of Las Vegas gambling addicts. It introduced me to Park Avenue philanthropists and Ukranian hit men, to the quest for beauty and the shock of violence, to good intentions gone disastrously wrong and bad intentions gone absurdly good. It took me from a mother’s love to a father’s hate to a friend’s loyalty (or was it betrayal?) to a boy who comes of age through unthinkable adversity that, thanks to the seamless writing, we experience right along with him. (From a safe remove, of course. Which is how I like to experience adversity.)

So that, I would say, is my definition of a good book: one that brings me to people who are totally different, but really kind of the same, as me.

And aren’t they all?